Locally Grown Classical Music

Is there a "right and proper" way to experience the Arts? There is a school of thought out there that may suggest that experience can connect us with a singular truth. If you watch a play you should experience one specific emotion. The third act of a Chekov should always give you a feeling of surprise even though you saw the gun in the first act. Monet’s painting of lilies should always make you feel calm and serene even if you had a traumatic experience as a child that involved lilies and you have never recovered from the experience. It is this feeling that there is one interpretation and one truth that the experience of the art connects you with.

One of the challenges of the arts is that they feel removed, above the common people, and somewhat snobby. Folks in tweed jackets like to tell you what the experience and the interpretation is supposed to be, adding to the feelings and sense of separation between the intelligentsia and the hoi polloi. Yet I believe that the arts are important for all people because they speak to a greater reality, a shared experience, and a way of living that we all encounter in a unifying way but can allow for a diversity of the experiences of the individual. The arts, when liberated from the constricting interpretations and demands of the ivory tower, can offer an experience of truth that is specific to the individual experiencing the music/painting, etc. And I believe that what the arts can do, religion and the experience of worship can do as well, if one is deliberate about it.

I’m going to use Antonín Dvořák’s Serenade for Winds (Op. 44/B.77) as an illustration of my argument.

A young and dapper Dvorak

Dvorak’s work was written in 1878, so we are placed in the height of the Romantic Period of music. I’m not going to give a full excurses of the Romantic Period, but some of the main characteristics are important to be aware of. Most of the information that I will be using is taken from Leon Plantinga’s chapter about the context and time of Romantic Music from his book aptly titled, Romantic Music. Let’s remember that the Romantic period begins around the time of revolutions in France and in the American Colonies. People started to embrace these crazy ideas of thinking for themselves, of being autonomous and free, and of throwing off the shackles of monarchy. The philosophical enlightenment project is in full force calling people stop blindly accepting the teachings of authority (including the church) and instead to realize how we are all out own master of our own life. The middle class is coming into its own with the rise of textiles and mills and the nearing of the industrial revolution (of which greatest production was novels by Dickens). In the music world, it was a time when music publishing become prominent, putting music in the hands of the “ordinary people,” when opera houses were being built making it possible for the “ordinary person” to attend opera (why they would want to, I don’t know). Music was moving from the upper class to an emerging middle class, setting up the stage for the American Bandstand Top 40 in about 100 years or so. Philosophically, the notion of “aesthetics” emerged drawing thinkers to wonder and contemplate the merits and purpose of the fine arts. The fine arts were becoming less disconnected from the “ordinary people” and placed more in their hands.

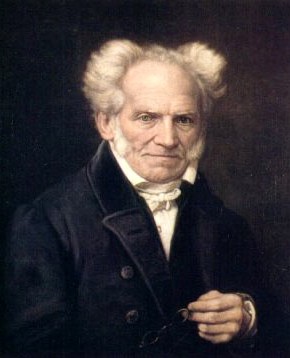

In addition to all of your standard enlightenment discourse, Arthur Schopenhauer (known for his dashing good looks and winning personality) wondered and wrote about the notion of “realness,” the “Idea” which he would claim is (more or less) the basis of all reality.

Schopenhauer looking even more dapper and dashing!

It is more that what we can know or see or immediately experience. Schopenhauer suggested that art allows us to see beyond the particularities of things to the fundamental level of reality and to know and experience the “Idea” in its fullest (even if it is only for a moment). It was a way to connect people with The Real as it is (which is not necessarily what can be seen but what is known or experienced). There is much more to it than this tight, little line, but I’m not going to get into the nuances and intricacies’ of Schopenhauer’s thoughts and writings. Suffice it to say, for Schopenhauer, art (specifically music) served the purpose of connecting people with something greater than themselves: a truth and reality of existence.

So we have the Romantic period of the fine arts including music. People were expressing their emotions, connecting with nature, loving pathos, and having deep, brooding thoughts and feelings. Men were sighing deep sighs, having moments of existential angst and wondering what the purpose of it all might be. Women were wondering how it is that they could express the beauty of the moment, the perfection of the star or the wave or those feelings of infatuation that they have towards that tall dark stranger sitting in the corner. Blake and Wordsworth and Shelly and Coleridge and Byron and Keats were pouring their pain and love and hope and joy into their writings. Truth was out there, waiting to be experienced in all of its deep longing and joy. But Truth was monolithic.

If you listen to composers of the Romantic period, folks like Mendelssohn, Liszt, Chopin, Schumann, Berlioz, Verdi, and Wagner, you will hear thick, lush chords, rich melodies that are deep with emotional content whether it be joy or sorrow or longing or bliss. A flair for the dramatic (especially with Berlioz and Wagner, and maybe Verdi as well) is also a part of this time. People were rising up to claim their independence and doing it with gusto. The individual was emerging in a way that demanded to be taken seriously. Music connected all of these experiences, the waves of change, the pull for meaning with a reality and an existence that if not giving meaning at least gave a sense of connection with something bigger. Or at least this is what Schopenhauer was claiming. As the autonomous self was emerging, there was a sense of connection through the arts.

So bring into this context and ethos Dvořák, at the height of the Romantic era. Dvořák was born in Bohemia to a rhapsody so beautiful that some are still singing it today (not true). As a composer he was successful in his own time, traveling throughout Europe, spending some time in America, including Spillville, Iowa (which he apparently enjoyed…good for you, Iowa). He was respected by Brahms and was influenced by Wagner. His music is considered conservative when compared with the harmonic chances that Wagner takes, the longing pathos expressed by Chopin, the virtuosic bravado of Liszt or the ego-mania of Berlioz and Wagner, but it is good. Plantinga described his music as retrospective in style, having a clear tonality, and expected modulations. This is a nicer way of saying that Dvořák is safe and predictable, the kind of composer you would want to take home to meet your parents. So does Dvořák connect with the Truth that Schopenhauer is speaking about or is he so safe that such a Truth is avoided?

There is something more to Dvořák. He is a composer of his people. He was a Czech composer and carried with him the songs of the Bohemian landscape. The folk songs, the music he grew up with never left him, and influenced the melodies, the rhythms, and the harmonies of his work. While some may have tried to remove themselves from the influence of folk tunes, Dvořák embraced them and we may argue that he embraced the Truth of them. He never forgot who he was and who his people were. Let it be known that this is not a new idea or a new path that Dvořák was forging. Instead, it is a notion that many people have considered in describing Dvorak as a “nationalistic” composer. Yet I want to consider it with Schopenhauer in the background and with a specific piece of music.

Back to the Serenade for Winds. It is a great piece of work, not only for that ensemble (two clarinets, two oboes, two bassoons, three French horns, cello, and double bass) but on its own it stands as a brilliant piece of musical writing. After its premier in 1878 Johannes Brahms took time away from growing and grooming his beard to call it Dvořák’s greatest work to date. It was something that Dvořák wrote in 14 days, making the rest of us look lazy and slovenly. Some have suggested that it was perhaps hearing Mozart’s Serenade for Winds in B flat Major that influenced Dvořák’s work – more on that in a moment.

(This next section speaks to the specific movements and themes of the piece. If you aren’t into that kind of thing, then skip ahead to the conclusion… but you will miss something life-changing!)

The piece starts with a grand and stately march, a fanfare feeling rhythmically as well as melodically. It demands your attention, telling you that something important is happening. Yet the second theme in this movement is light, and delicate in a falling, pastoral sense. We have a stately march transitioning to a moment of sweet descending cascades of notes in the clarinets, bassoons, and then the oboes. It is a lovely contrast perhaps harkening to a sense of Sturm and Drang (although no self-respecting Music Historian would ever suggest so). Finally the movement ends with the march, calling people to their feet in attention for whatever might be next.

The second movement harkens to the Mazurka, a Czech dance. It pulls the listener to remember the folk dances of Bohemia, of the hills of that land, even if he or she was never from that place. It speaks to a simplistic time and place, to a dance that is relaxed, easy, and enjoyable. That is until the clarinets go crazy with a repetition of notes pulling the ensemble into the trio section of this Slovak waltz. The clarinets take one beat and make that the driving force the focus of the middle part of the movement, demanding an almost frantic version of the dance. Then, as true to the waltz form (and other trio movements) the first dance returns in its pastoral fashion, giving everyone a chance to catch their breath and breath.

The third movement recalls Mozart’s Serenade for Winds, with the horns’ lilting rhythms and the sparse melodic call and response between the clarinet and the oboe. It is almost as if Dvořák is paying tribute to the master who influenced this very piece. The movement is structured like an inverted arch, growing and falling into a deep, bass-heavy climax in the middle and then easing away through the rest of the movement.

Finally, in the fourth movement we have a frantic and frenetic dance that moves in spits and starts. It begins in controls the space and sound, and then all the melody, all the motion falls apart as if anticipating something great, and yet nothing happens. The melody that does emerge is one of searching, of longing, of a question that is never fully answered but is shared by the oboes, the clarinets, the bassoons, and even the cello and double bass. Another Slavic dance interrupts the questions trying to make things light, but it is not enough and the frenetic dance returns demanding again attention and returning to the question. A pastoral theme slows things down a little, but again it is not enough and the frenetic pace returns to the question. And then things seem to fall apart. The melody becomes sparse, the volume decreases to almost a whisper and yet the intensity has not abated. Then, in a moment of triumph, the march from the first movement returns calling people to their feet in respect and admiration and celebration for Bohemia and all of the Czech culture and people. The movement ends in flourishing finale as one would expect in the romantic style of music.

I encourage you to find a recording of this piece or hear it live, it really is a profound and wonderful experience.

(And now… the stunning conclusion)

Let’s return to the bigger picture and conversation that I am drawing from Schopenhauer and the Romantic ideals that we have been considering. What I think Dvořák is doing with this piece (as well as with many of his other works) is connecting with Reality, with the “Idea-in-itself,” but in a very particular way. Dvořák is not universalizing the experience of the listener in a monolithic “Truth” kind of way, but making it particular to his own experience and to the reality of the Slavonic experience. His first and second movements harken back to his homeland, to the melodies and the experience that he and others had and he is inviting his listeners to join him in this encounter. I would argue that his third movement is not so much an homage to Mozart, but an invitation for others to experience that very thing that Dvořák experienced when he heard that great master’s work. It is a connection to the tradition of music that Dvořák has embraced, a very deliberate tip of the hat as well as a deep connection with the experience that classical music (broadly understood) offers. We could go further and consider that perhaps the march itself speaks to a sense of victory and hope, but now we are dancing dangerously near the place of forcing and contriving the work to fit the purpose I want. Maybe I have been doing that all along, but lets not be overt; it is all about subtlety.

Schopenhauer speaks of the way in which music connects with the “idea-in-itself” and had a very singular notion of this connection. He was steeped in the enlightenment project and the modernistic notion that there is a Truth out there just waiting to be discovered. In Dvořák I believe that we can find a notion that instead there are truths, a multiple of experiences, a multiple of ways to be moved and connected. Dvořák does not connect someone with simply the Truth, but instead the “truth” as it is experienced in Bohemia, as it has been heard and celebrated by the Czechs, and as it has been offered in the “Slavonic style.” I would argue that this occurs with all art. There is a particularity to the context of the artist that engages the particularity of the recipient and in that engagement a truth is found. It may or may not correspond with a broader “truth” if any such thing exists. Good art moves the recipient to an experience but not “The Experience.”

Here is the theological bit:

In the religious world there are many arguments about the “right and proper” way of worship. We have all, without knowing it, embraced Schopenhauer’s notion that there is a reality, an “thing-in-itself” that is out there and many would say that there is one right way to connect and many wrong ways to worship and connect. Hence some have removed the organ and put in the praise band claiming that this would be the only way to really connect. Others have worshipped in fear of the overhead screen and instead looked to their hymnbooks claiming that it is only through the hymns that the truth of the diving can be experienced. Some cling to liturgy and others to a loose and relaxed feeling of worship. Many would claim that they are right in what they do and connect with the truth of God in the best and most proper way. Would we tell Dvořák that he was not a real composer because of his use of Slavonic themes, melodies, and rhythms in classical music? Would we say that he does not connect us with a Truth as well as Wagner or Schumann does? My hope is that through looking at his work we see that instead of one way and one Truth, there are a multiple of experiences of Truth to be found and maybe multiple truths to be experienced. Perhaps the same is with worship. While Catholics and Baptists are both worshipping the same God and find hope in the same Christ, there is a difference in the experience of Christ that one will find in a Baptist service than with a Catholic service. And that is ok. It is ok for a community to be true to its roots, to pay respect to where it came from. It is also ok to push oneself harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically (so to speak). Dvořák learned other traditions, he traveled to America, and spent time in Iowa of all places, and allowed others to influence his music. Yet he never forgot his roots and Truth of his context that shaped and formed him.

With worship, there are multiple ways of encountering and experiencing the divine, there is not one fullness to Truth and no one has the best way to connect with it. Yet each community has it’s roots, it’s identity and should remember it’s roots. As with the arts, there is not one Truth or one right and proper experience. Dvořák was staying true to who he was, just as Brahms did and Chopin did and many others. We are called to do the same, but still push ourselves, try other things, and continue searching and looking for ways we can deepen and enhance our connecting and experience of God. There is not one right way to experience the divine, but stay true to who you are as you continue to search and try.